The US, Turkey, Russin and Syria. Why this matters.

Anyone who has been following the events in Syria and the region over recent years would not deny that the stalemate in the northern regions of the country is not unexpected. After more than a year of negotiations – most of them without much effect or emotion – the United States and Turkey continue to fail to resolve their differences with regard to the establishment of the so-called “buffer zone” along the Turkish-Syrian border. President Recep Erdogan has repeatedly stressed that his country intends to intervene in northern and north-eastern Syria to secure its territory from possible penetration by PKK forces, currently part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, a Washington-backed coalition. The latest threats for an offensive came just as Ambassador James Jeffrey was visiting Ankara to hold talks on Syria. Immediately afterwards, a US military delegation arrived in the Turkish capital and a long closed-door debate began on what could be done from now on.

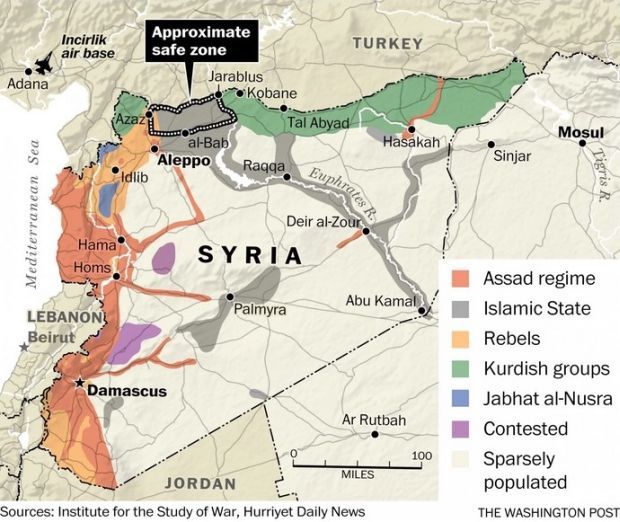

The risk of Turkish intervention is high as is clear to any expert observer. The accumulation of military force has been going on for months. Ankara is sending reinforcements to rebel areas in northern Syria, where it has bases, while diplomatic moves are taking place to seek support, including among the Russian administration, which is also interested in what is happening in northeast Syria. An intervention would make the engagements of the US and its allies much more difficult to achieve, including the continued military operations against Islamic State.

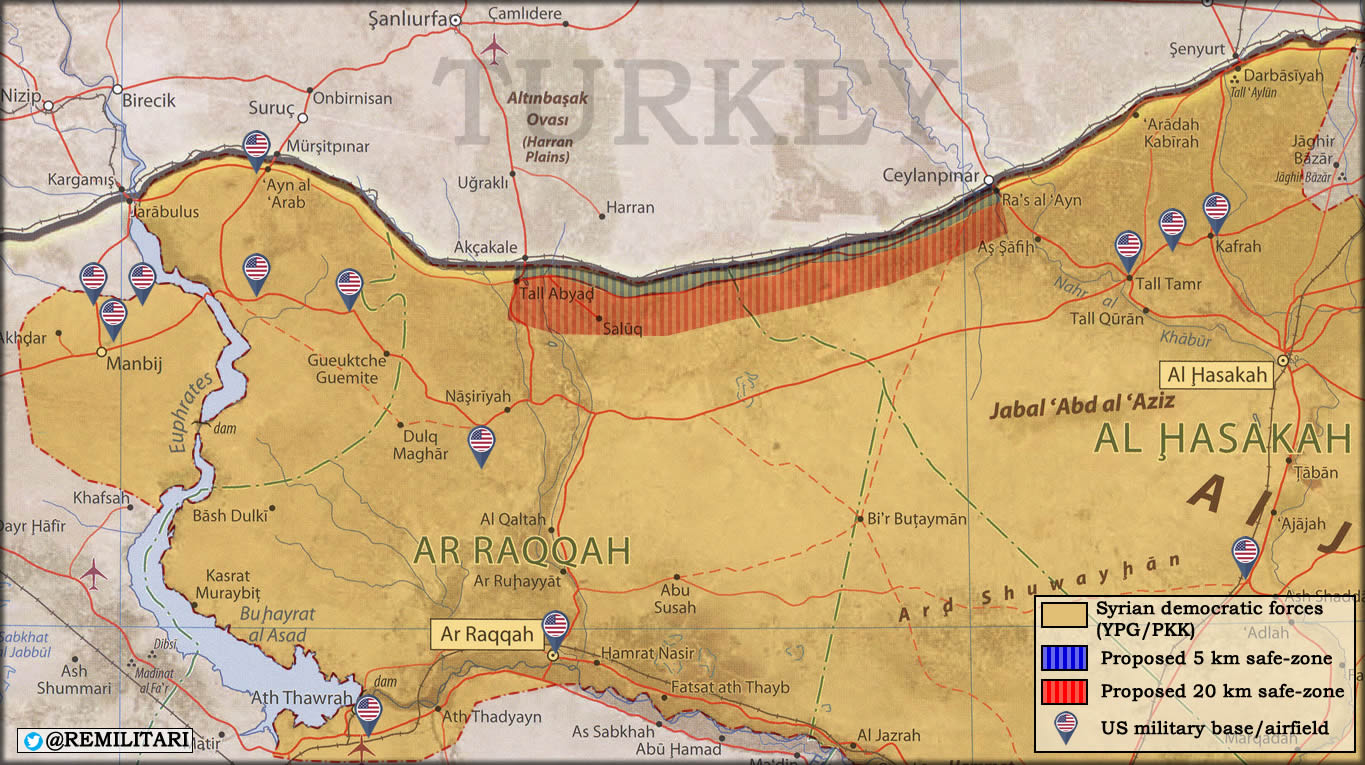

In the talks with the US on Northeast Syria, Turkey has called for the establishment of a 32km zone into Syrian territory, extending from the Euphrates River to the Syrian-Turkish border. The US is attempting to counter Ankara’s proposal in favour of establishing a territory in which Turkish presence will be restricted, patrols will be US-Turkish, and Kurdish militias will be withdrawn outside of this zone which will stretch 5 to 14 km into Syrian territory. This major difference of opinion stems from the difference in perceptions of threats and interests in Syria – on the one hand are Ankara’s concerns about empowering Kurdish militias, and on the other, Washington’s concerns about Islamic State. This major divide has troubled the two NATO allies since the end of 2014, and despite nearly half a decade of negotiations, neither country can offer the other a compromise that satisfies each country’s core national interests. This difference in goals has been dividing these two NATO allies since 2014.

At the heart of the divergences between the US and Turkey is the fact that each country has a different concept of regional security. Both sides see the other as a major destabilizing factor in the Middle East. Although both Ankara and Washington are willing to hold talks, especially given the fact that they have the two largest armies in NATO, they are not really interested in compromises because each country considers its interests in Syria more important than the other’s. This detail is particularly important in understanding the deterioration in US-Turkey relations.

US-Turkish talks on establishing a buffer zone in northeast Syria date back to late 2018, when, after a phone call with Erdogan, Donald Trump opposed his advisers and announced that he would support Erdogan’s proposal which took the form of an initial offer aimed at paving the way for the major offer – Turkey taking control of the area, replacing European and American troops stationed in north-eastern Syria with Turkish troops. This proposal also has a specific political and military objective – if Turkey manages to establish itself in this zone, it will cause the United States to begin the severing of its relations with the Kurdish militias, part of which has been a member of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party which since 1984 has been at war with Ankara. For the Turkish administration, the proposal would solve two problems – the crunching of the far-left Kurdish militias and the removal of the remaining Islamic State cells in eastern Syria, which continued to operate after the occupation of their territories.

The delay in the implementation of this proposal ultimately turned against Turkish interests. This allowed members of the Trump administration to persuade the US President to cancel his orders for withdrawal of US forces and leave about 1,000 troops, who along with British and French forces, are assisting the Syrian Democratic Forces. The challenges remain for Turkey, and Ankara is increasingly trying to apply pressure, including threats that it will carry out unilateral attacks in north-eastern Syria if Washington prefers to support Kurdish Marxist groups instead of its NATO ally.

What Turkey has to offer is close to the ongoing negotiations for the city of Manbij, a Syrian town with a predominantly Arab population, located on the Euphrates River and currently under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces. In June 2018, after months of Turkish threats to attack, Washington and Ankara reached an agreement on the so-called Road map to Manbij. The plan includes three steps that should address differences in the stances for the control over this region. In the first stage, Washington and Ankara will have separate patrols, then joint patrols, and finally reform the city’s institutions, limiting the involvement of PKK members. Except for the mechanisms of the agreement, in actual fact neither Turkey nor the United States have agreed on the major parts of the text, making the Roadmap unusable, so tensions have been building ever since.

After all, differences and a lack of adequate negotiations are likely to lead to small-scale military operations on Turkey’s border with Syria. In fact, such a move is of strategic importance for Ankara. For if the Turkish army manages to seize Tal Abyad and Kobane cities located in the border area, this could later be used to demand more concessions from the US. There have already been reports of tensions around Tal Abyad, and for at least a year the exchange of artillery fire between the Kurds and the Turkish border forces has been intensifying. Such a military step will not cost so much and therefore it won’t weigh on the budget – respectively, it does not carry a serious risk of discontent among the Turkish general public. Such a strategy, however, could cause fire on Turkish territory and resulting civilian casualties.

It is unclear how the US and Turkey can reach a compromise in the current situation and in the near future. Even public statements of friendship mean nothing at the moment, as the accumulation of military equipment is apparent. The Trump administration ultimately decided to stay in Syria to work for its own interests and to support the Syrian Democratic Forces. Turkey and the United States are countries with strong distrust of each other, despite their historic commitment to NATO. This is the reality now and it will not change any time soon. A compromise would mean Ankara accepting the American outlook on the Syrian Democratic Forces, which would be too much for Turkey. A compromise means that the Turkish administration must accept a military alliance as a legitimate player, not a terrorist group whose leaders want to attack Turkey. The US is currently facing two choices – either its ally in NATO or its partner in Syria.

And then there is Idlib.

The area, which is lately absent in international news, is an arena of severe collisions and intense air strikes from the Russian air forces. While regional players are fighting for the future of one or another part of Syria, nearly 1,000 civilians have died since April as a result of the Syrian regime offensive in north-western Syria. More than 400,000 people have been displaced, further exacerbating the humanitarian situation in Idlib, which already houses more than 3 million people – many of them displaced from other areas in Syria. One of the reasons Turkey wants to establish a zone in northern Syria is precisely Ankara’s desire to ease the pressure on its border by returning refugees from its territory back to Syria.

Despite numerous talks in Kazakhstan, there is no ceasefire in Idlib. More than 50,000 rebels are gearing up for a massive military offensive that is backed by Russia. Idlib is also a hot spot between Ankara, Washington, Assad and Russia. Turkey has stated that it will be patient with the United States, though not for long, and the Assad regime uses almost the same words for Turkey, defining it as an occupying force. Just a year ago, Turkey and Russia signed an agreement under which Ankara should force insurgents to drop their weapons and the regime would stop its offensive in return. None of this has been implemented, and in fact the agreement has never really come into force. The Syrian regime itself is also hostile to the Kurds and the Syrian Democratic Forces, with Damascus politicians calling for a purge from the Euphrates to the border with Iraq.

Russia has been watching impatiently the disputes between Americans and Turks as Moscow itself is facing a dilemma. If Ankara decides to intervene, Russia will support the Syrian regime in its demands that the Turkish army withdraws from the conquered areas, not out of love for the Kurds, but to fulfil its commitment to consolidate Assad’s position, who on his part is seeking to return all Syrian territories under his control. However, such an outcome would affect Kremlin’s image in Ankara, where C-400 systems were recently purchased despite protests by NATO and the US.

While Russia, Turkey and the US keep on testing how far tensions in Idlib and the Kurdish territories will go, Syrians continue to be killed and displaced from their homes. Humanitarian organizations have been blocked or pushed out entirely because of diplomatic stalemate, and optimism is nowhere to be seen.

Meanwhile, other parts of Syria keep reminding of themselves. Old rebel and activist groups have become active in southern Syria. Dozens of officers from Syrian government forces have been killed in Daraa and Damascus over the past six months in attacks attributed to insurgents. Iranian militias in the area are under pressure from Israel on the one hand, which is conducting regular air strikes in the border area with Syria and from Russia on the other. Moscow does not intend to give Tehran leeway, because for the Kremlin, Syria is a Russian zone of influence.

While Turkey and the US are busy disagreeing with each other, Russia and Iran have entered a fierce competition process for gaining influence, Israel is closely monitoring the Iranians, rebels are intensifying their actions in their former territories that Assad seized during the past year, Kurds are preparing for a Turkish intervention, and the Islamic State is using the ensued chaos to its advantage as it is anything but destroyed. In this situation, making diplomatic, military and political decisions will become increasingly difficult for all players in Syria