Now Lets see how Trump handles Chinas push in the South China Sea

Vietnam repeated its demand that a Chinese survey ship and its escorts leave contested waters in the South China Sea as Beijing’s lifting of a ban on fishing in the area threatened to raise tensions further.

The presence of Haiyang Dizhi 8 (which means Marine Geology 8) and a coast guard escort in the Vietnamese-controlled waters over the past month has already caused the most protracted standoff between the two countries in five years.

Its return to the waters around Vanguard bank on Thursday – following a brief departure for Chinese controlled waters – had already risked inflaming the situation.

“Vietnam has made contact with China to protest its repeated violations and demanded that China withdraw the vessel group from Vietnamese waters,” Le Thi Thu Hang, a spokeswoman for the country’s foreign ministry, said on Friday.

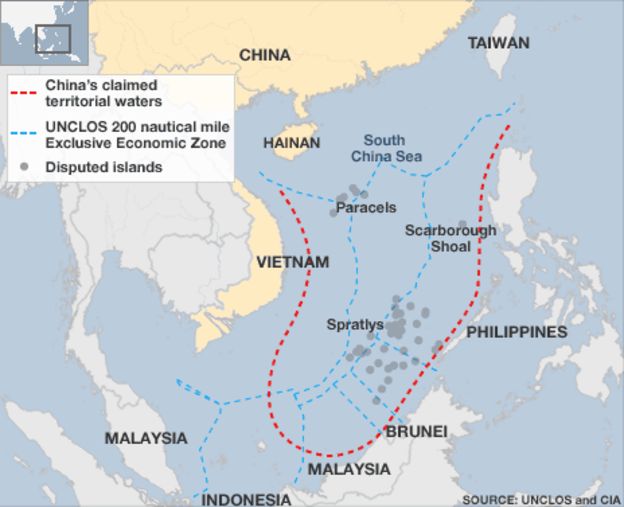

The decision on Friday to lift the annual fishing ban in parts of the South China Sea – which means hundreds of fishing vessels from southern China are likely to head for the Gulf of Tonlin and contested waters around the Paracel Islands and Scarborough Shoal – increases the risk of further confrontation .

The fishing ban had been in place since May and ended at noon on Friday, prompting grand ceremonies along the coast of southern China to mark the departure of the fleets.

In Sanya, on the southern tip of Hainan island, more than 300 fishing boats left Yazhou Central Fishing Port on Friday afternoon, while in Yangjiang, a coastal city in Guangdong, around 800 fishing boats headed out to sea, news portal hinews.cn reported.

While Beijing has said the two-decade old fishing ban can improve marine ecology and maintain sustainable fishing, the measure has long been rejected by Vietnam, the most vocal critic of China’s increasingly assertive stance in the controversial maritime region.

Observers said the lifting of the fishing restriction could intensify Beijing-Hanoi friction in the wake of the confrontations in the Vanguard Bank, a Vietnamese-controlled part of the Spratly chain that began in July when Haiyang Dizhi 8 entered the waters.

On Thursday it returned to the area, having briefly left for Chinese-controlled waters, escorted by at least five coast guard ships, Reuters reported citing data from the website Marine Traffic. It was being tracked by at least two Vietnamese navy vessels.

“Vietnam will take [the removal of the ban] as an opportunity to ramp up criticism of China’s ‘invasive behaviour’, which could further complicate bilateral relations and magnify the negative perception of China,” said Zhang Mingliang, an associate professor at Jinan University in Guangzhou and South China Sea studies specialist.

China claims sovereignty over most of the resource-rich South China Sea but its assertion is contested by neighbouring countries, with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei all having their own overlapping claims.

Fishing rights have become one of the most contentious issues between China and the other claimants, as reserves in the contested waters, once home to 3,365 species of fish, dwindle as a result of overfishing as well as dredging and construction work mostly carried out by China.

But Zhang said the rival claimants have little room to find a way out of the competition over fishing rights.

“As all the claimants have linked the fishing issues together with the territorial disputes, fishing – which used to be an economic issue that related to the livelihood of the fishermen in the region – has now become a complicated political dispute,” Zhang said.

In an example of how fishing is being politicised, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who is facing a strong backlash over his friendly ties with Beijing, recently withdrew from a verbal agreement he said he had made with Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2016 that allowed Chinese fishermen in disputed waters around Reed Bank.

China and the Philippines have discussed jointly exploring for oil and gas in the area at the tip of the Spratly Islands.

“This means the fishing issue, combined with international and domestic politics, is [so] complicated that it is almost impossible to reach any formal fishing cooperation [agreement],” Zhang said.

Observers in the region said that as competition over fishing rights intensifies, the risk of conflict is growing.

Heightened nationalistic sentiment is driving fishermen to act aggressively, according to Collin Koh, a research fellow at Singapore's S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Another source of potential conflict could come from coastguard vessels that China, Vietnam and other countries have used to advance their territorial demands in the region.

But Zhang said that while China and Vietnam both have strengthened their coastguard capacity significantly in recent years, the two countries may be reluctant to deploy those forces in fishing disputes, which are seen as less of a priority than incidents such as the Haiyang Dizhi 8 standoff

“As the capacity of coastguards is limited to both sides, [China] is less likely to send coastguard vessels to protect fishing boats now as it is protecting the survey ship,” Zhang said.